By Lisa R Marshall

The King & I

I would probably have been six or so, when I was given my first clutch of Ladybird books – it was a truly random collection. There was, ‘The Big Pancake’, ‘The Enormous Turnip’, ‘The Three Billy Goats Gruff’ – and thrown in for good measure, to see if I was still paying attention, ‘King John and Magna Carta.’

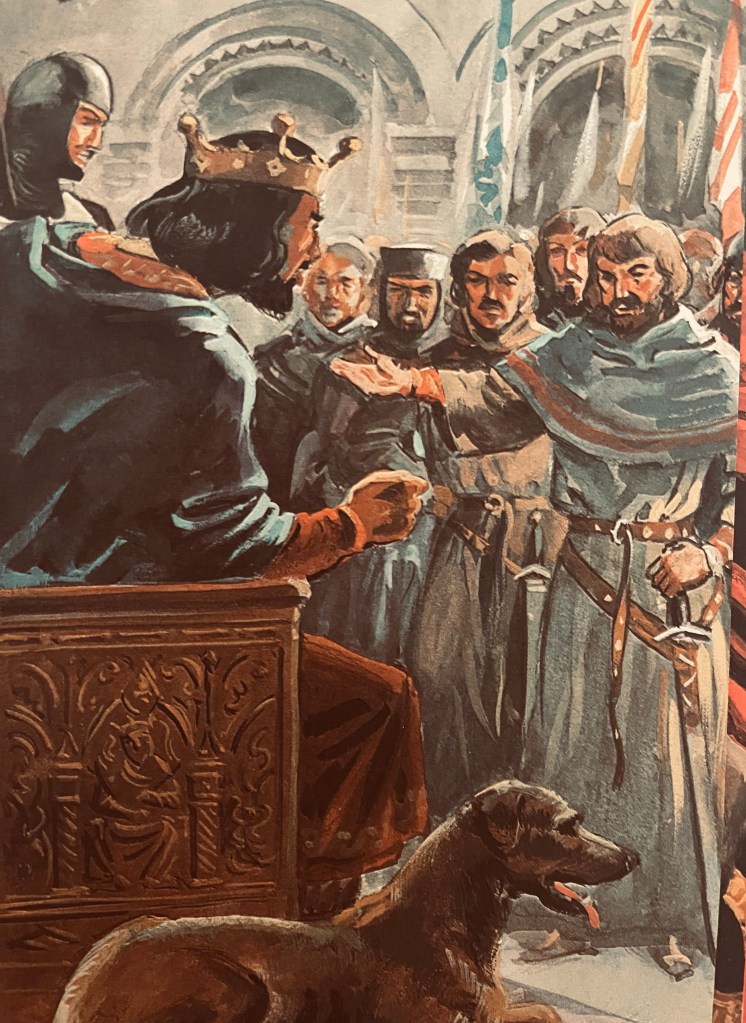

The cover of the latter was instantly intriguing to me, depicting a fuming looking King John with a large document being foisted upon him. He did not look anywhere near the signing stage. Behind him, looking on rather expectantly, a motley collection of onlookers gather at a designated, safe distance.

The book started strongly.

“John was probably the worst King to ever occupy the throne of England. He tried to deceive everybody, and was trusted by none. His reign was disastrous, but it remains one of the most important in the history of the English speaking world. This book will tell you why.”

A very direct kick off for my first history book. One of many to come and I treasured it.

A few years later, on a local school trip to Worcester Cathedral – I found myself up close and personal with the the tomb of King John. Somewhat taken aback, I remember asking the teacher, if this was, the ‘real one.’ I remember being quite blown away that there was a dead King of England, a coach ride away from my house. Not just any King but the infamous John.

I’ve since been back to see John many times. We have history.

Recently, I was listening to a back episode of the ‘Rest is History’ podcast (an addiction, presented by historians, Tom Holland and ‘Man of The Shires’ (Bridgnorth to be exact) – Dominic Sandbrook.) The episode focused on the Magna Carta with historian Ted Vallance describing how John has been called, the “first memorable wicked Uncle in English history”, prompting me once more to reflect on John and on something I had never really understood. Why was he buried in Worcester?

‘Infamy, infamy’ – Why is John so infamous?

The chapter dedicated to King John in Tracy Borman’s excellent, ‘Crown and Sceptre’ is simply titled, ‘A Very Bad Man.’ Simple as?

John ruled from 1199 to 1216 and was the youngest of Henry II’s and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s five sons, therefore never seemingly destined for the crown. However, the deaths of his older brothers led him there, with John succeeding from older brother Richard.

That was of course Richard I, that original ‘three lions on his shirt’ Knight King who had died fighting in France having been caught by an crossbow bolt to the shoulder. He of ‘Lionheart’ fame to be cast forever in bronze, sword aloft on horseback and placed outside the Houses of Parliament by romantic Victorians.

Bit of a hard act to follow? Interestingly, historian Simon Schama wrote that he thought the two brothers had more in common than, “the cartoon stereotypes allow for”, that they were both violent, vain and given to “ornamental excess.”

Historian Dan Jones writes in ‘The Plantagenets’, that John’s accession to the throne in 1199 was met with immediate concern as the Prince’s track record had been, “pockmarked by ugly instances of treachery, frivolity and disaster.” That treachery had included conspiracy against the Lionheart himself – another chapter in the long Plantagenet game of thrones which was to get catastrophically worse in the years to come.

John’s accession also met with familiar French complications. Richard and John’s nephew Arthur, Duke of Brittany, had gained support for his own claim to the English crown, leading a rebellion in Normandy and had crucially gained the support of the French King, Philip II. However, it was to all end very badly for young Arthur.

Dan Jones recounts the story of his capture, stating it was, ‘highly likely’ that following his imprisonment, John murdered Arthur with his own hands and had his body cast into the Seine. Yikes. In his own dramatic reimagining, Shakespeare has young Arthur throwing himself off the ramparts of a castle to escape the wrath of John, with a cry of, “Heaven take my soul, and England keep my bones!”(King John, Act 4, Sc3).

Whatever the grisly truth, Arthur was gone.

Back home, King John’s interesting tax policies were seeding resentment. Cue trouble with England’s powerful, armed landowning Barons. Rebellion was brewing, London had became a rebel stronghold – wouldn’t be the last time. The lands in France would not be regained and at huge cost, with John eventually being forced to face a final showdown with the Barons, in a field at Runnymede alongside the Thames in June 1215.

John was presented with the ‘Magna Carta’ to sign, this ‘great charter’ of 63 clauses aiming to bring John to account, ranging widely from influential clauses on a free man’s right to justice under the law, to seemingly other burning issues such as the need for standardised drinking measures. It was to be a landmark moment in English history. Schama goes on to write, ‘if Magna Carta was not the birth certificate of freedom, it was the death certificate of despotism.”

But despite the theatre of the signing at Runnymede, distrust of the King was off the scale and remained there. True to form John soon wanted the document annulled. Civil war ensued. Invasion came across the Channel. Everything kicked off.

However, by October 1216 – John was dead.

He had succumbed to dysentery, caught it was said, following a disastrous and poorly judged attempt to cross the tidal Wash near Lincoln. His baggage train and rumoured crown jewels were said to have been washed away in the waters, with horses being swept into whirlpools and quicksands, in a scene reminiscent of Tolkien. According to accounts read by Jones, this included the loss of John’s, “portable chapel” and what Schama describes as John’s, “travelling windows.” Modern metal detectorists have driven themselves into a frenzy searching for these lost riches, to no avail. Yet.

Following his death, rumours that John had in fact died from eating poisoned peaches, cider, plums or even poison from a toad can’t be proven. Shakespeare fuelled these rumours with lines spoken by John on his death bed (actually sat in a death chair no doubt to aid play staging.)

“ Poison’d- ill fare! Dead, forsook and cast off” and, “There is so hot a summer in my bosom /That all my bowels crumble up to dust.” (King John, William Shakespeare, Act 5, Sc 7).

Crikey.

Tracy Borman doesn’t mince her words as she sums up John’s reign, “one of the worst kings ever to occupy the throne of England.” Ouch.

“At Worcester must his body be interr’d/ For so he will’d it.” (King John, Act 5, Sc 7 – William Shakespeare)

According to wishes expressed in his will, the King’s body was taken from Newark Castle in Nottinghamshire where he had died and laid to rest in Worcester Cathedral.

John remains there in a tomb dated from 1232, commissioned by his son Henry III and placed close to and facing the high altar – a sacred spot – the oldest royal effigy in England. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, the architectural historian, called the effigy, “one of the finest of its time in England.”

John had specifically requested he be buried near to the revered (since destroyed) Anglo-Saxon shrines of St Wulfstan and St Oswald, his tomb marked with the Plantaganet badge of the Three Lions (or strictly the Three Leopards as the cathedral’s web site points out).

The Purbeck marble effigy of the King is designed as an actual likeness, said to be unusual for the times. John is also holding an unsheathed sword in his left hand, the symbolism of which is unclear. His eyes are wide open whilst those of the saints next to him are closed in prayer. Originally, the effigy had semi-precious stones, now long missing. At its base, there is a carved lion, turning to bite the bent end of his sword – some argue that this depicts a lion of England defending itself against the King. As his son commissioned the effigy, this symbolism may be questionable. However it is indeed a curious sight.

The opening of King John’s Tomb

More surprisingly, the tomb has been opened at least twice.

The British Library holds a record of the second official recorded opening of the King’s tomb in 1797, undertaken by the wonderfully named, Valentine Green, who had been researching the city of Worcester as part of a key historical survey.

Green had, “strong assumptions of conjecture,” that John may have actually been buried elsewhere in the Church (pleased to say not under the car park). In his account, Green goes to some lengths to explain he wasn’t the only one who had the opinion that John was actually buried in the Lady’s Chapel.

The doubters and Green were of course wrong, as he was to write in his account of the tomb opening,

“On taking down the panel at the head and one on each side, and clearing out the rubbish, two strong elm boards were originally joined by a batten nailed at each end of them …. were next discovered, and upon their removal, the stone coffin, of which they had formed the covering, containing the remains of King John became visible!”

He seemed surprised. Green, the exact polar opposite of our modern day King locater, Philippa Langley.

Following the discovery, the chaplain and a pre-eminent local surgeon were summoned to oversee and record the discovery. Green writes that the body was in the exact same position as the figure on the tomb, that John had 4 teeth with no caries (fillings), though his upper jaw was peculiarly placed near his elbow.

The fact about the jaw bone is a rather fascinating detail, interestingly, in another ‘Rest is History’ podcast on ‘Stonehenge and Ancient Ritual’, Professor Ronald Hutton remarks on a ancient burial where jaw bones had been removed in a similar way. He remarks that this was sometimes thought to have been deliberately performed to allow the deceased to be able to speak more freely after death or actually, in the case of witch burials, to prevent the dead speaking or being able to utter curses.

Other fascinating details recounted by Green was that, grey hair could be seen ‘under the covering of the head,’ with the body covered with the fragments of a decayed crimson damask robe, which was said to be similar to the garment as shown on the carving of the tomb itself.

Another key discovery was the remains of a sword in a scabbard and a monk’s cowl covering the King’s skull, which Green writes would have been placed on him, “ as a passport through the regions of purgatory.” Well I think it would have been reasonable for John to have expected a rough ride there.

Another interesting detail from Green’s account was that he was unsure, whether fragments of material found near the King’s feet was evidence that he had been buried wearing boots, or whether they were a, “part of under dress familiar to modern pantaloons.” Really?

The opportunity was also taken of measuring John, who was found to be five foot six and a half inches. Green ends his account by stating, that the fact that this was King John was “fully proved.”

So yes, eleven year old me – this was really him.

The King’s remains were then put on public display for two days in a macabre spectacle which Green admits was so popular with the public it became ‘ungovernable.’ He ends, “On the evening of the Tuesday the 18th July, the day after it had been taken down, and the royal remains laid open to the view of some thousands of spectators, who crowded the cathedral to see it, the tomb of King John was completely restored and fully closed.”

What a relief.

The Cathedral’s library holds a number of key objects on John, including the original will – said to be the oldest copy of a royal will in England, his thumb bone and a fragment of his burial clothes. Worcester’s City Museum also has some of John’s teeth which were lent to the British Library in 2015 to be exhibited to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta – the King would definitely not have been amused.

Why Worcester?

John had apparently made as many as nine visits to the city, including, two visits at Christmas. The Ladybird history book mentions such a visit with John attending, “a gathering of the Great Council at Worcester” in 1214. John was also described as loving to hunt at the nearby Royal Forest of Kinver, though from reading his story, it’s hard to see where he would have got the time.

For John, burial in what was now rebel held parts of England would have become problematic, making Beaulieu Abbey and London unwelcoming options.

It was also likely that a desire to be close to those landmark Anglo Saxon shrines influenced John, shrines that would have held such fascination and devotion at the time he lived. The cathedral’s guidebook also recounts that he was recorded as having prayed for some time at St Wulfstan’s shrine when he visited in 1207, also stating John provided money for the repair of the cloister and monastic buildings.

These bejewelled and painted shrines were sadly lost in 1538, with the bones of the saints moved and buried somewhere north of the altar. It was unlikely these shrines were ever going to survive either the Reformation itself or the Puritan led vandalism of the cathedral that would follow later.

The inclusion of carvings of the two saints alongside the head of the King on the effigy, speaks volumes. They could not be placed any closer, saintly security guards for eternity. It puts me in mind of a line from one of Richard II’s famous speeches, “I’ll give/ my subjects for a pair of carved saints.” (King Richard II, Act 3, S3 – William Shakespeare.)

Wulfstan had died in 1095 and been canonised in John’s reign, playing an active role in the rebuilding of many of the local great abbeys as well as the cathedral itself after damage in conflict. He had been a bishop before and after the Norman Conquest, and was said to have cured Anglo Saxon King Harold’s daughter of sickness and was described as, “‘the one sole survivor of the old Fathers of the English people.”

Oswald had died in Worcester in 992 and was noted for his work to promote the clergy and scholarship in England as well as of his works to help the poor. Following his death, various miracles were reported at his burial place.

But whatever the key factor, it’s a serene and spacious resting place for an infamous King of old England. Here John has centre stage.

Worcester Cathedral is sat regally overlooking that glorious River, the Severn. Inside and despite the nearby roads its a very peaceful ancient space. What drew John, draws us.

Since that first school trip, Worcester Cathedral has been one of my favourite places in England. There is something in the calm history soaked air of the place.

So our very own ‘very bad man’ is here to stay.

The tomb remains thankfully very firmly sealed and rests under the watchful eye of that other John, the Bishop of Worcester.

King John receives visitors daily as does the Cathedral – maybe just avoid discussing missing teeth, taxes, poisoned peaches or the Magna Carta, when you pass by.

Written by Lisa R Marshall

- Sources and Suggested Further Reading/Listening:

- King John and Magna Carta (A Ladybird Adventure from History Book) – L. Du Garde Peach with illustrations by John Kenney (Wills & Hepworth Ltd, 1969)

- Crown and Sceptre – Tracy Borman (Hodder, 2021)

- The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England- Dan Jones (William Collins, 2012)

- A History of Britain: At the Edge of the World? – Simon Schama (BBC Worldwide Ltd, 2000)

- Worcester Cathedral web site http://www.worcestercathedral.co.uk and ‘King John and Worcester Cathedral – A Pocket Guide.’ Available from the cathedral shop.

- The Buildings of England – Worcestershire – Nikolaus Pevsner (Penguin, 1968)

- The Rest is History Podcast Episode 62: Magna Carta (Goalhanger Podcasts)

- The Rest is History Podcast Episode 114 : Stonehenge, ancient ritual and the origins of Paganism (Goalhanger podcasts)

- An account of the discovery of the body of King John in the Cathedral Church of Worcester, July 17 1797 – Valentine Green (British Library)

- Cathedral photographs by Lisa R Marshall

Very interesting. Local history bought to life. Well done and a very enjoyable read

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating! Worcester Cathedral is a fantastic place to spend time. It’s an outstanding physical reminder of Worcestershire’s rich history and the part it played (and plays) in our nation’s journey.

Love that this article was inspired by a Ladybird book.

LikeLiked by 2 people